ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Mortality Attributable to Tobacco Consumption in the

Province of Buenos Aires. Estimation from the National

Surveys of Risk Factors

Mortalidad atribuible al consumo de tabaco en la

Provincia de Buenos Aires. Estimación a partir de las Encuestas Nacionales de

Factores de Riesgo

Andrés

G. Bolzán1, Hanna Fritz Heck1, Silvia

Rey2

1 Department of Epidemiology and Control of Outbreaks. Ministry of

Health of the Province of Buenos Aires.

2 Provincial Tobacco Control

Program. Ministry of Health of the Province of Buenos Aires

Address for reprints: Andrés G Bolzán.

andresguillermobolzan@gmail.com.

Nicaragua 5825, 1° A (1414), Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires.

Rev Argent Cardiol 2023;9:187-194. http://dx.doi.org/10.7775/rac.v91.i3.20630

SEE RELATED ARTICLE: Rev Argent Cardiol 2023:91:172-173. http://dx.doi.org/10.7775/rac.v91.i3.20644

ABSTRACT

Background: Tobacco consumption is the leading

cause of death from non-communicable diseases, such as heart disease, lung

disease and cancer. Estimating prevalence-based mortality attributed to tobacco

consumption is based on prior knowledge of the number of smokers, ex-smokers,

and non-smokers in the population. These data derive from the four National

Surveys of Risk Factors (Encuestas Nacionales de Factores de Riesgo, ENFR).

Objectives: This study aims to show the burden

of mortality due to tobacco consumption in the Province of Buenos Aires in the

assessed periods of the four ENFRs (2005, 2009, 2013, 2018).

Methods: Mortality attributable to tobacco

consumption was estimated by using a prevalence-based method and assuming the

risks associated with smoking in the 19 causes classified as associated with

smoking, in accordance with the Cancer Prevention Study II (CPSII). The deaths

were grouped into periods equivalent to those relevant

to each ENFR. The CSPII attributable fractions were

then applied by estimating the absolute deaths and attributable fractions of

mortality by cause and groupings: tumours,

circulatory diseases and respiratory diseases.

Results: Overall, in persons aged 18 years

or older, there was a decrease in smoking prevalence from 29.5% in 2005 to

23.1% in 2018 (an absolute reduction of 6.4% and a percentage reduction of

21.7%). A total of 6293 out of 18 255 deaths from cardiovascular diseases in

the four surveys were attributed to smoking, that is, 34.4%, compared to 68% of

deaths from tumours and 40.0% of deaths from

respiratory diseases.

Conclusion: It is necessary to further

strengthen measures to reduce exposure to tobacco.

Keywords: Tobacco - Mortality - Attributable Risk

RESUMEN

Introducción:

El consumo de tabaco es

la principal causa de defunción por enfermedades no transmisibles como las

cardiopatías, las neumopatías y el cáncer. Estimar la

mortalidad atribuida al consumo de tabaco dependiente de su prevalencia se basa

en el conocimiento previo del número de fumadores, exfumadores

y no fumadores en la población. Estos datos provienen de las cuatro Encuestas

Nacionales de Factores de Riesgo (ENFR).

Objetivos:

El presente trabajo

pretende mostrar la carga de mortalidad por consumo de tabaco en la Provincia

de Buenos Aires en los períodos de relevamiento de las cuatro ENFR

(2005-2009-2013-2018).

Material

y métodos: La

mortalidad atribuible fue calculada utilizando un método dependiente de la

prevalencia, y asumiendo los riesgos asociados al consumo en las 19 causas

clasificadas como asociadas al tabaquismo según el estudio Cancer

Prevention Study II

(CPSII). Las defunciones fueron agrupadas en períodos equivalentes a los

relevamientos de cada ENFR. Las fracciones atribuibles del CSPII se aplicaron

entonces calculando las defunciones absolutas y atribuibles de mortalidad por

causa y sus agrupamientos: tumores, circulatorias y respiratorias.

Resultados:

Globalmente, para todas

las edades de 18 años y más, se pasó de una prevalencia de tabaquismo del 29,5%

en 2005 al 23,1% en 2018 (reducción absoluta de 6,4% y porcentual del 21,7%).

De las 18 255 muertes producidas por enfermedades cardiovasculares coincidentes

con los cuatro relevamientos, 6293 fueron atribuibles al tabaquismo (34,4%),

frente al 68% de las muertes por tumores y el 40% de las muertes de causa

respiratoria.

Conclusión:

Se hace necesario

fortalecer aún medidas para reducir la exposición al tabaco.

Palabras

clave: Tabaco -

Mortalidad - Riesgo atribuible

Received: 03/07/2023

Accepted: 05/24/2023

INTRODUCTION

Smoking is one of the leading causes of morbidity and

mortality. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), tobacco

consumption is the leading cause of death from non-communicable diseases, such

as heart disease, lung disease and cancer. (1) Global figures show that tobacco consumption causes

more than 7 million deaths each year, of which more than 6 million are smokers

and about 890 000 are non-smokers exposed to second-hand smoke. Almost 80% of

more than 1 billion smokers in the world live in low- or middle-income

countries. (2) In Argentina, more than 44 500 people die annually from smoking-related

diseases and these deaths represent 13.2% of all deaths occurring in people

older than 35 years, mainly due to cardiovascular diseases, chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease (COPD) and lung cancer. (3) Based on the evidence from a large number of studies

on the effects of tobacco consumption, several methods have been proposed to

measure it and estimate the burden of disease. In our country, four National

Surveys on Risk Factors (Encuestas Nacionales sobre Factores de Riesgo, ENFR) have

been performed in 2005, 2009, 2013 and 2018, in which, among other aspects, tobacco

consumption has been measured based on the population's statements about their

status as smokers, non-smokers or ex-smokers. (4-7) Since 1980, the impact estimate of different risk

factors on population mortality by applying epidemiological methods has become

frequent in Anglo-Saxon countries, mainly in the United States. To estimate

mortality attributable to different risk factors, several methods are available,

which vary in terms of both data required and acceptance of assumptions. These

methods are mainly based on the concept of the population attributable

fraction, that is, the percentage of cases that could be prevented if exposure

to the risk factor under study was removed. To estimate mortality attributed to

tobacco consumption, different calculation processes are identified, (8) which may be classified

according to whether they are dependent or independent of smoking prevalence,

that is, whether or not smoking prevalence is used to estimate the mortality

burden. The application of a prevalence-based method to estimate attributed

mortality is based on prior knowledge of the number of smokers, ex-smokers and

non-smokers in the population. These data derive from the four ENFRs. The

present work aims to show the burden of mortality due to tobacco consumption in

the Province of Buenos Aires in the survey periods of the four ENFRs.

METHODS

Mortality attributable to tobacco consumption was

calculated by using a prevalence-based method and assuming the risks associated

with tobacco consumption according to the Cancer Prevention Study II (CPSII). (9) Two data sources were

available for its implementation:

1. Calculation of the prevalence of tobacco

consumption: smokers, ex-smokers and non-smokers for men and women by risk age

groups: 35-64 years old and 65 years or older. The data sources were the ENFR microdata bases: 2005/2009/2013/2018 from the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INDEC; the

National Institute of Statistics and Censuses in Argentina). (7)

2. Table of observed mortality by age group and sex

according to the cause of death. The database was that containing overall

mortality data from 2005 to 2018 reported by the Dirección

Provincial de Estadísticas de la Salud

(DIS; Provincial Department of Health Statistics) of the Province of Buenos

Aires.

Statistical analysis

1. Prevalence of tobacco consumption: the microdata bases of the ENFRs were exported to SPSS

(Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) and the prevalences

were calculated by the survey year and by risk groups (age and sex). The

results published by the INDEC for each ENFR served as control, so that, the

overall estimates should be consistent with those published. Point values and

confidence intervals were calculated for complex samples by using the weighting

factors provided by the database.

2. Observed mortality: DIS’s databases were exported

to SPSS and deaths by smoking-related cause were calculated according to the risk

group (age and sex). The calculation was performed using the following formula:

AM = OM*FAP, where PAF =

[p0 + p1RR1 + p2RR2]-1 / [p0 +

p1RR1 + p2RR2]

AM means attributable mortality; OM, observed mortality

(number of deaths by cause, age and sex); PAF, population attributable

fraction; p0, p1, and p2 represent the prevalence of non-smokers, smokers and

ex-smokers, respectively; RR1 and RR2 represent the relative risk in smokers

and ex-smokers, respectively. Each p value was calculated for each ENFR

adjusted for age group and sex.

Variables: 1–Risk groups: Age of 35-64 years and 65 years or

older. These categories are established in the CPSII. 2–Tobacco consumption:

The document used was that published by the INDEC for the management of the

ENFR databases. It classifies tobacco consumption variable into three

categories: smoker, ex-smoker, and non-smoker. 3– Cause of death: It was

classified according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10th

Revision. Individual data on age, sex and cause of death were assigned for each

of the diseases in the CPSII model. Deaths and tobacco consumption prevalences were grouped into four periods

equivalent to each ENFR. The CPSII attributable

fractions were applied considering those cut-off points. Similarly, specific

mortality rates were calculated by risk age group and sex for the total of each

set of diseases associated with tobacco consumption: tumours,

cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, from the list of tobacco-attributable

causes according to the model. The population used as denominator to estimate

the overall death rates was based on the demographic projections for the

Province of Buenos Aires published by the DIS. This led to observe the

evolution of the raw death rates by age group and sex for each annual period

evaluated. The statistical softwares Epi Dat 4.2 and SPSS 20 were

used.

Ethical considerations

This study considers grouped data. Patients were not

individualized

RESULTS

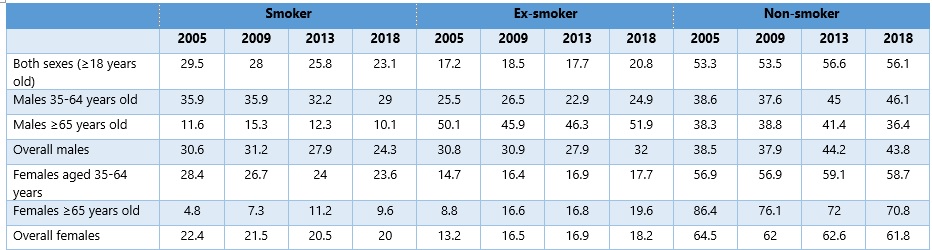

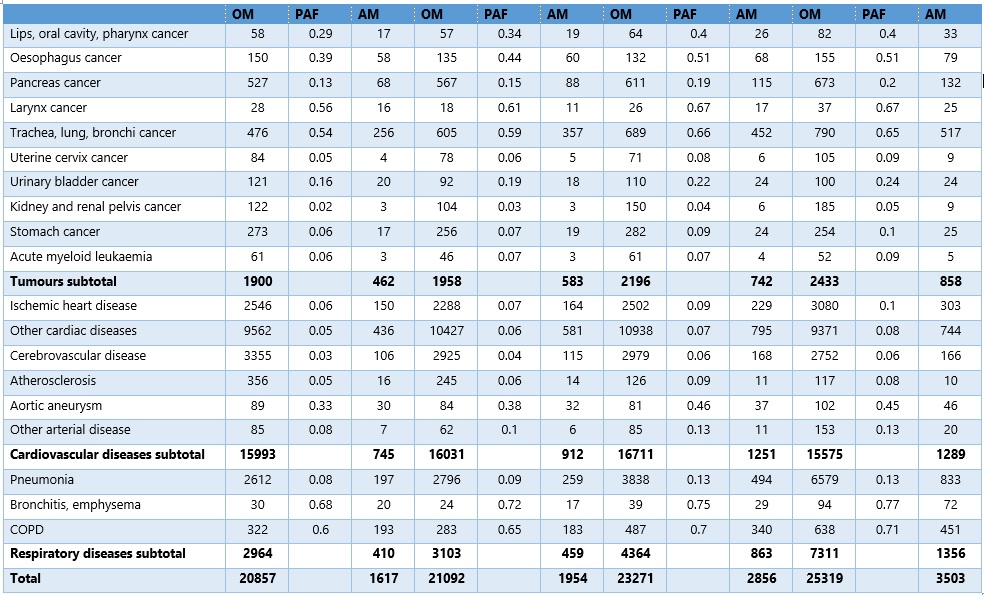

In Table 1, the prevalences of tobacco

consumption by sex and age according to each one of the four ENFR estimates are

shown. In Tables

2 to 5,

absolute deaths and attributable mortality fractions

by cause and groupings in persons aged 35 years or older are shown. Overall,

there was a decrease in smoking prevalence from 29.5% in 2005 to 23.1% in 2018

(absolute reduction of 6.4%, and percentage reduction of 21.7%). The prevalence

of ex-smokers increased from 17.2% in 2005 to 17.7% in 2018; expressed in inhabitants,

from 1 673 861 to 1 925 674 (251 813 more). There were 223 925 deaths recorded

within the 19 smoking-related causes, 51 890 (23.1%) of which were attributed

to smoking. Of these, 36 690 (70%) were men and 15 200 (30%) were women.

Table 1. Prevalence

of tobacco consumption (%) as per the ENFRs performed in the Province of Buenos

Aires

ENFR: Encuesta Nacional de Factores de Riesgo (National Survey on Risk Factors)

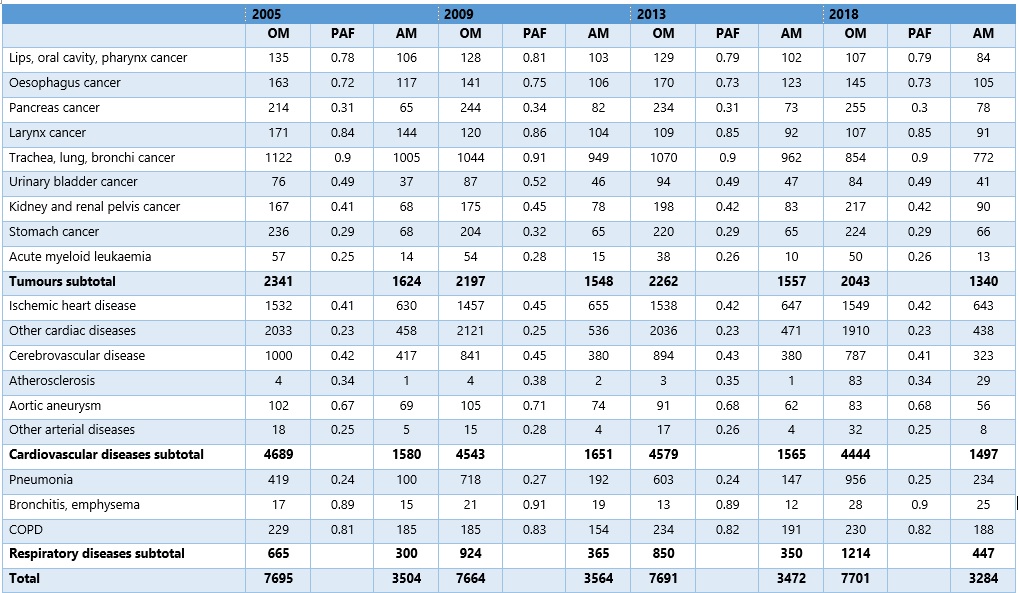

Table 2. Mortality attributable to tobacco consumption in males aged 35-64

years. Province of Buenos Aires. ENFR series: 2005,

2009, 2013, 2018

AM: attributable mortality; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease; ENFR: Encuesta Nacional

de Factores de Riesgo

(National Survey on Risk Factors); OM: observed mortality; PAF: population

attributable fraction

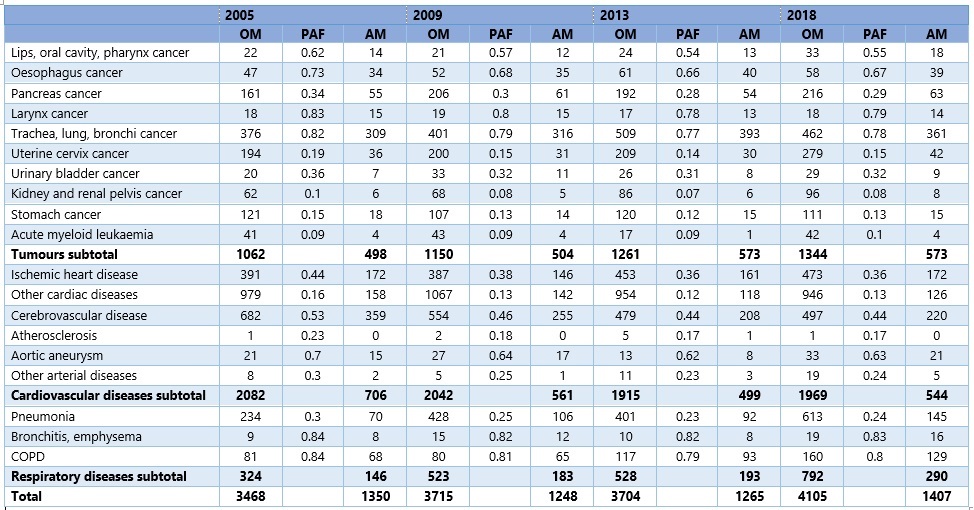

Table 3. Mortality attributable to tobacco consumption in females aged 35-64

years. Province of Buenos Aires. ENFR series: 2005,

2009, 2013, 2018

AM: attributable mortality; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease; ENFR: Encuesta Nacional

de Factores de Riesgo

(National Survey on Risk Factors); OM: observed mortality; PAF: population

attributable fraction

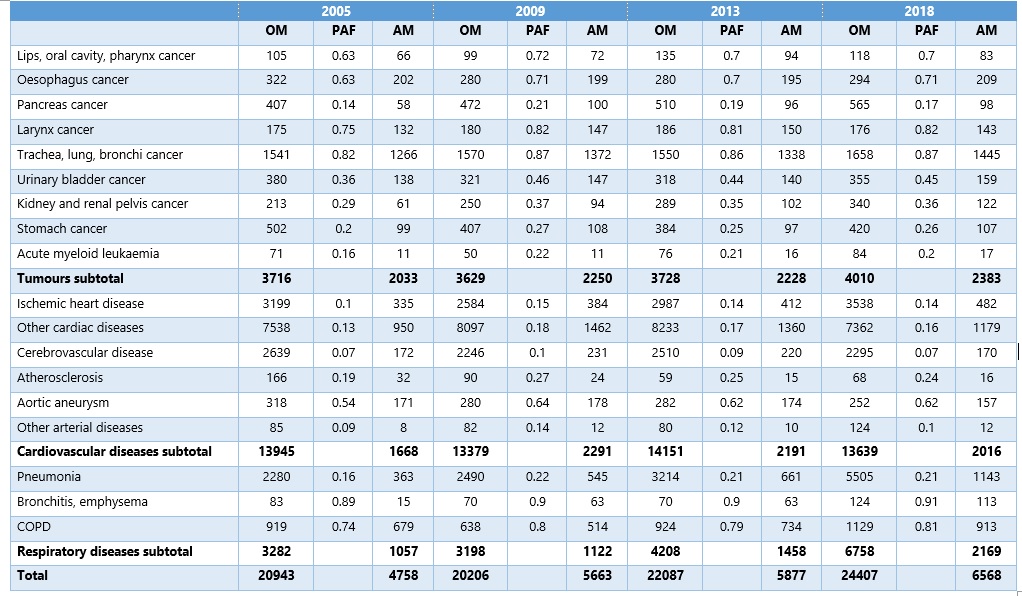

Table 4. Mortality attributable to tobacco consumption in males aged >64

years. Province of Buenos Aires. ENFR series: 2005,

2009, 2013, 2018

AM: attributable mortality; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease; ENFR: Encuesta Nacional

de Factores de Riesgo

(National Survey on Risk Factors); OM: observed mortality; PAF: population

attributable fraction

Table 5. Mortality attributable to tobacco consumption in females aged >64

years. Province of Buenos Aires. ENFR series: 2005,

2009, 2013, 2018

AM: attributable mortality; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease; ENFR: Encuesta Nacional

de Factores de Riesgo

(National Survey on Risk Factors); OM: observed mortality; PAF: population

attributable fraction

The leading cause of death from smoking-related tumours included trachea, lung and bronchi cancer. Among

men aged 35-64 years, 90% of tumours were attributed

to tobacco; 3688 out of 4090 deaths in the four years analysed

were attributed to smoking. As regards laryngeal cancer, 431 out of 507 deaths

in the four years analysed were attributed to smoking.

In men aged 35-64 years, overall cardiovascular diseases represented 18 255

deaths, 6293 of which were attributed to tobacco consumption (34%). In the case

of respiratory diseases in men aged 35-64 years, 1462 out of the 3653 deaths

were attributed to tobacco consumption (40%), and in the case of smoking-attributable

pneumonia, 673 out of 2696 deaths were attributed to tobacco consumption

(24.9%). In this age group and sex, COPD has not modified its incidence or

death rates or its attributable fraction. Out of 878

cumulative deaths, 718 (81.7%) were attributed to tobacco consumption. In men

older than 64 years, there is a trend towards a reduction in mortality

attributable to all smoking-related tumours. Lung,

trachea and bronchi cancer produced 6319 deaths in the four cumulative years,

5417 of which were attributed to smoking (85%). Regarding laryngeal cancer, the

second tumour with the second highest attributable

fraction, 572 out of 717 cumulative deaths were attributed to smoking (79.5%). In the group of cardiovascular diseases in men older than 64 years,

8166 out of 55 114 cumulative deaths were attributed to smoking (14.8%).

The largest fraction attributable to smoking was that of aortic aneurysm: 680

out of 1132 deaths (60%). In absolute terms, the highest mortality was observed

in the group of other cardiac diseases with accounting for 31230 deaths, 4951

of which were attributed to smoking (15.9%). In the case of respiratory

diseases, 5806 out of 17 446 deaths in men older than 64 years were caused by

tobacco consumption (33.2%).

In women aged 35-64 years, there was

a cumulative total of 4817 deaths from smoking-related tumours

in the four years analysed, 2148 of which were

directly attributed to smoking (45%). Laryngeal cancer presented the highest

PAF: 57 out of 72 deaths in the four years analysed

could have been prevented with smoking control. Trachea, lung and bronchi

cancer represented 1748 deaths, 1379 of which were attributed to tobacco

consumption. Oesophagus tumours

and lip and oral cavity cancer presented PAFs near 60%. Smoking-attributable

mortality due to heart disease showed a decrease from 2005 (29.1 per 100 000)

to 2018 (18.7 per 100 000), a 35.5% reduction. In total, there were 8008 deaths

from cardiovascular causes in women aged 35-64 years during the four cumulative

years, 2310 of which were attributed to smoking (28%). Cerebrovascular disease

shows the highest attributable fraction: 47% (1042 out of 2212 cumulative

deaths were attributed to smoking). This was followed by ischemic heart disease

(1704 deaths in the four years, 38.2% attributed to smoking). Although the

group of other cardiac diseases produced a greater number of deaths, only 13.7%

out of 3946 cumulative deaths in the four years analysed

were attributed to smoking. As regards smoking-related respiratory diseases in

women aged 35-64 years, 37.4% out of 2167 deaths were attributed to smoking.

Women aged 65 years or older were the group with the highest increase in

tobacco consumption in the Province of Buenos Aires. Among them, death rate

resulting from smoking-related tumours has increased

concomitantly. If we consider the rates of all

smoking-related tumours and we focus exclusively on

smoking-attributable death rates, the increased from 49.9 per 100 000 in 2005

to 75.9 per 100 000 in 2018. Out of 8487 deaths from cancer in women

aged 65 years or older accumulated in the four years analysed,

2644 were attributed to smoking (31%). Lung, trachea and bronchi cancer

resulted in 2560 deaths in women aged 65 years or older in the four years analysed, 1582 attributed to smoking (62%). Death rate resulting from these tumours

increased from 51.4 per 100 000 in 2005 to 69.9 per 100 000 in 2018. In

the case of lip and oral cavity cancer, there were 261 deaths, 36.3%

attributable to smoking. Cardiovascular diseases in women aged 65 years or

older represented 64 310 deaths, 4195 attributable to smoking (3.7%).

DISCUSSION

The

presumption that tobacco consumption was a risk factor for health emerged in

1920. It was only until 1980 that the grounds for

estimating the smoking impact on mortality were made explicit by means of

epidemiological methods. (8,10) CPSII is a

cohort study conducted by the American Cancer Society which began in September

of 1982. (9) CPSII limits the causes of death attributable to

smoking to 19 and identifies them under the heading "established causal

relationship". Estimation of attributed mortality using a prevalence-based

method is the simplest calculation procedure in terms of data availability.

This method, the most widely used in the scientific literature to estimate

tobacco-attributable mortality, which has been implemented in the CDC's SAMMEC

(Smoking Attributable Mortality Morbidity and Economic Cost) software, is

commonly used for the serial estimation of tobacco-attributable mortality in

the United States, and its use is widely spread. (11,12) To properly

estimate and use modelling, it is necessary to know

the excess risk of death of those exposed (smokers and/or ex-smokers), data

that may be collected from a cohort study. (13) In 2008, the WHO adopted a set of

practical and cost-effective measures to strengthen the implementation of the

main provisions on demand reduction under the WHO Framework Convention on

Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC): the MPOWER measures. Each measure corresponds to at

least one provision of the WHO FCTC. (1,2) The six

MPOWER measures are the following: •To monitor the consumption of tobacco and

the prevention measures. •To protect population from tobacco smoke. •To offer

help to people to quit smoking. •To warn of dangers associated with smoking.

•To enforce prohibitions on advertising, promotion and sponsorship. •To increase

tobacco taxes. It is necessary to strengthen these and other promotion and

prevention measures in order to reduce exposure to tobacco. If tobacco

consumption could be reduced to zero (obviously an unrealistic but ideal

scenario), 19 756 deaths due to tobacco-related tumours,

20 966 deaths related to cardiovascular causes and 11 168 deaths related to

pneumonia, bronchitis and COPD would have been avoided in the province of

Buenos Aires; in other words, 51 890 deaths occurred in the four years analysed. This represents 23.1% of the total 223 925 deaths

derived from the 19 causes attributable to tobacco consumption. In contrast to

the analysis focused exclusively on adjusted death rates, smoking-attributable

mortality indicates the magnitude of the risk factor burden on mortality. (14,15) The PAF magnitude of death due to

tobacco consumption continues being a challenge for public health, mainly

because of the burden of disease and the demand on health services. (16)

Particularly, in America, the estimates of healthcare costs have yielded 33

billion dollars directly, which is equivalent to 0.7% of the Gross Domestic

Product of the region. (17) Similarly, tax burden on tobacco

industry does not directly cover healthcare costs, which in Argentina have been

calculated at 37%. Although the studies are not numerous, they have estimated

the burden of attributable mortality in the country (as in the Province of

Tucumán) (18) showing that 4.1% of deaths could be attributed to

smoking, which is lower than the data recently reported for Argentina (14%). (3) It is

necessary to measure the magnitude of the situation by considering the

percentage of reduction that could be expected not only for the total number of

deaths, but specifically for the causes associated with tobacco consumption,

because there, the burden of smoking is clearly more significant. (19,20)

CONCLUSIONS

Prevalence studies like this have

important limitations: they assume the risks linearly as weighting factors of a

population group, whereas covariables are completely

unknown. Similarly, other epidemiological weighting factors are left outside

the estimates. The ENFRs have weaknesses since the measurement of habits are

self-reported. Nevertheless, in many cases, they are the only potential large

models to estimate the burden of disease from recognized risk factors.

Mortality attributable to smoking remains high and is unacceptable because

there are concrete possibilities for its reduction. It is necessary to further

strengthen measures to reduce exposure to tobacco.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

(See authors' conflict of interests forms on the web/Additional material).

![]() https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

© Revista Argentina

de Cardiología

1. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic: monitoring

tobacco use and prevention policies (2017). https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240032095

2. Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Estrategia y plan de

acción para fortalecer el control del tabaco en la región de las Américas

2018-2022. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/51575

3. Alcaraz A, Caporale J, Bardach A, Augustovski F, Pichón Riviere A. Carga de enfermedad atribuible al Tabaco en

Argentina y potencial impacto del aumento del precio a través de impuestos. Rev Panam Salud Pública 2016;40:204-12.

4. Segunda Encuesta Nacional de Factores de Riesgo para Enfermedades

No Transmisibles (Ministerio de Salud de la Nación Argentina) (2009).

5. Tercera Encuesta Nacional de Factores de Riesgo para Enfermedades

No Transmisibles (Ministerio de Salud de la Nación Argentina) (2013).

6. Negro E, Gerstner C, Depetris R, Barfuss A,González M, Williner

MR. Prevalencia de factores de riesgo de enfermedad cardiovascular en

estudiantes universitarios de Santa Fe (Argentina). Rev

Esp Nutr Hum Diet. 2018;22:131-40.

https://doi.org/10.14306/renhyd.22.2.427

7. Instituto Nacional De Estadísticas y Censo. Bases de Microdatos. Argentina: INDEC; 2021.

8. Martínez AM, Ríos MP, Otero JJG. Impacto del tabaquismo sobre

la mortalidad en España. MONOGRAFÍA TABACO. 2004; 16 (suplemento

2):75.

9. Office of the Surgeon General Office on Smoking and

Health Reports of the Surgeon General. The Health Consequences of Smoking: A

Report of the Surgeon General. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US);

2004. Available in https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44695/

10. Pérez-Ríos M, Montes A. Methodologies used to estimate

tobacco-attributable mortality: a review. BMC Public Health.

Jan 22 2008;8:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-22

11. Prevention CDC. Data from: Smoking-AttributableMortality,

Morbidity, and Economic Costs (SAMMEC) -Smoking-Attributable Expenditures

(SAE). 2020. Estados

Unidos de Norte America. Deposited August

13, 2020.

12. Conte

Grand M, Perel P, Pitarque R, Sanchez

G. Estimación del costo económico de la mortalidad atribuible al tabaco en la

Argentina. Ministerio de Salud de la Nación Argentina, 2003. Available in: https://bancos.salud.gob.ar/sites/default/files/2020-02/estimacion-costo-economico-tabaco-argentina.pdf

13. Allender S, Balakrishnan

R, Scarborough P, Webster P, Rayner M. The burden of smoking-related ill health in the UK. Tob Control. 2009;18:262-7. https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.2008.026294

14. Barrenechea GG, Cali RS. Mortalidad atribuible al tabaquismo

en Tucumán, Argentina 2001-2010. Medicina (B. Aires) 2016;76:287-93.

15. Rubinstein A, Colantonio L, Bardach A et al. Estimación de la carga de mortalidad por

enfermedades cardiovasculares atribuibles a factores de riesgo modificables en

Argentina. Rev Panam Salud

Publica 2010;27:237-45. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1020-49892010000400001

16. Figueroa M, Revollo G, Bustamante

MJ, Borsetti H, Alfaro Gomez

E. Distribución del riesgo cardiovascular en Argentina en 2018. Rev Argent Cardiol

2020;88:317-23. https://doi.org/10.7775/rac.es.v88.i4.17641

17. Pichon-Riviere

A, Bardach A, Augustovski

F, Alcaraz A, Reynales-Shigematsu LM, Teixeira Pinto

M et al. Impacto económico del tabaquismo en los sistemas de salud de América

Latina: un estudio en siete países y su extrapolación a nivel regional. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2016;40:213–21.

18. Barrenechea G, Cali R. Mortalidad atribuible al tabaquismo en

Tucumán, Argentina 2001-2010 Medicina (B. Aires) 2016;76:287-93.

19. Migliore

R. Sobre la disminución de los impuestos al tabaco y la no ratificación del

Convenio Antitabaco: ¿Cuál será el futuro del objetivo 25x25? Rev Argent Cardiol

2018;86:140-2. https://doi.org/10.7775/rac.es.v86.i2.13321

20. Ferrante D, Levy D, Peruga

A, Compton H, Romano E. The Role of public policies in reducing smoking

prevalence and deaths: the Argentina Tobacco Policy Simulation Model. Rev Panam Salud Publica/Pan

Am J Public Health 2007;21:37-49. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1020-49892007000100005